.

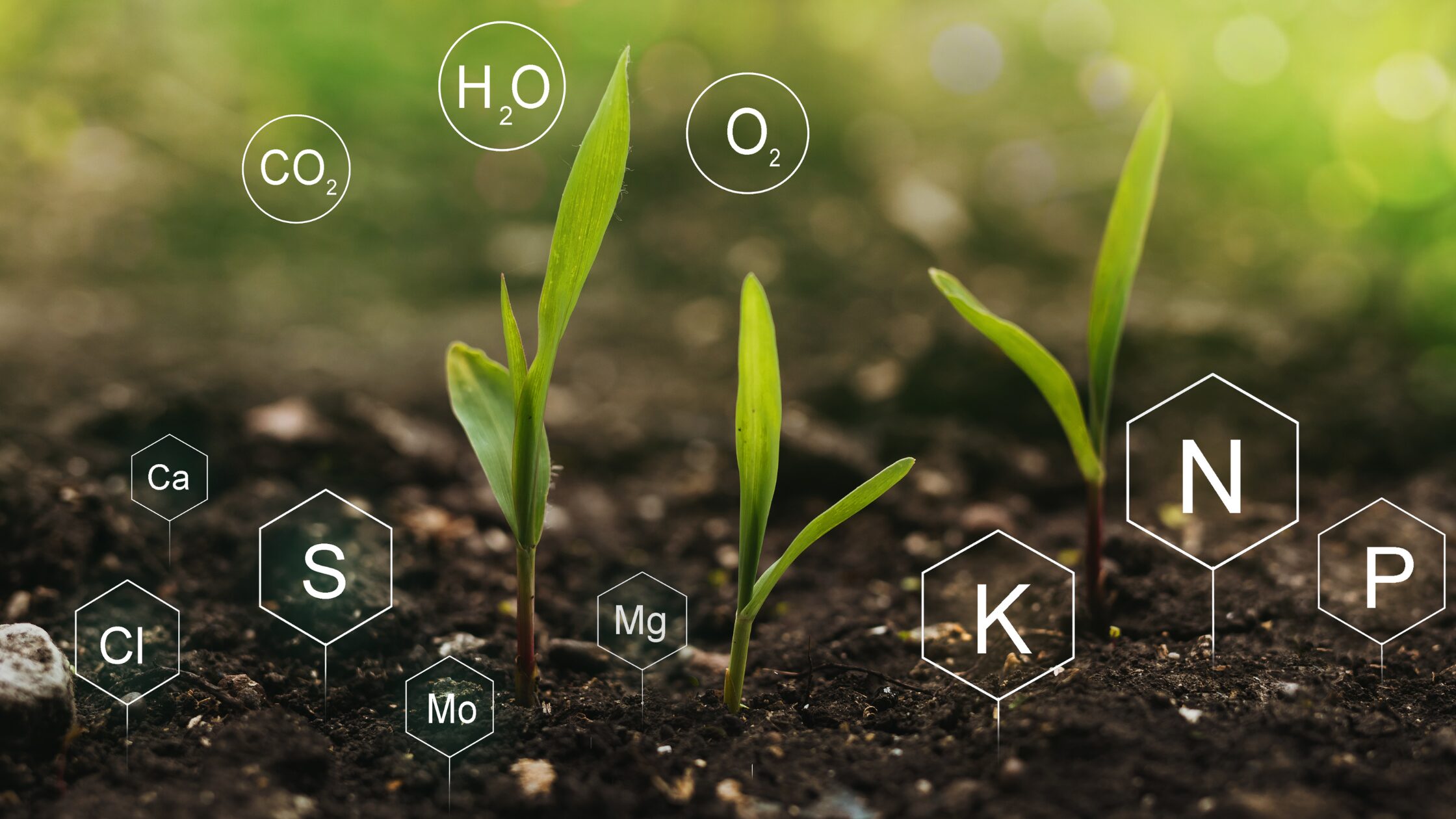

Plants are not unlike humans. To grow, thrive and stay healthy they need nutrition and sustenance. While for us fat, proteins and carbs are important, plants need different chemical elements for growth. The main part of a plant’s diet consists of carbon, oxygen and hydrogen which the plant can get out of the air and water. All other chemical components must be taken up as nutrients from the soil. When you know what those plant nutrients are you can provide your plants optimally, that is give them the right nutrients at the right time to make them grow, bloom and fruit lavishly.

Let’s have a closer look at the nutrients that plants need. We distinguish between macro- and micro-nutrients.

Plant nutrients: The Macros

The most important plant nutrients are called macro-nutrients. They include nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) but also magnesium (Mg), Calcium (Ca) and sulphur (S).

All plants need these nutrients in a relatively large amount, especially nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium.

Nitrogen (N)

Nitrogen is the most important nutrient for plants. It’s required in large amounts, is quickly used up and washes out easily off the soil when there is too much of it.

It’s not advisable to give too much nitrogen in one go. The plant won’t be able to consume it (or gets too much of it and becomes ill) and the excess will wash out into the groundwater.

Nitrogen is different from other nutrients as it’s mostly in the air. The air around us consists of about 2/3 of nitrogen. Nevertheless, the plants can only take it up via their roots. Bacteria and algae help the nitrogen get into the soil.

Insufficient nitrogen supply results in puny growth. The plants’ stalks and new shoots are weak, their leaves turn from a healthy green to yellow.

Nitrogen surplus results in excessive growth. The plants have thin stems and shoots and dark green leaves. They grow more leaves and less to no bloom. Nitrogen surplus makes the plant prone to illnesses and harms the storage time and the taste of your vegetables.

As nitrogen is a volatile nutrient (any excess washes or gasses out) it should be given continuously during the growing season but in low amounts. In spring and early summer, the plants need more of it. During summer, maintenance fertilisation can be carried out in lower doses according to the plants’ different demands.

Phosphorus (P)

Phosphorus can be found in the soil and water as salts, the phosphates. It influences the root system, growth, flowering, fruit formation and even photosynthesis.

It is more stable than nitrogen and is not as easily washed out of the soil.

Phosphorus deficiency is more rare than nitrogen deficiency.

Phosphorus deficiency results in a weakly developed root system and puny growth. Older leaves and leave stems turn red-brown-purple with a grey touch.

Phosphorus surplus prevents the plants from absorbing important micronutrients like iron and boron, resulting in a reduced growth. Soils with a high mull content are seldom low in phosphorus.

Potassium (K)

Potassium influences the metabolism and fluid balance. It supports fruit setting and improves resilience. A good availability of potassium also improves the quality and storage ability of fruits and vegetables.

Potassium deficiency makes the leaves dull and yellow-brown at the edges. A potassium surplus often leads to magnesium deficiency. Those two substances compete and hinder each other.

Sandy soils are more often prone to nutrient deficiency than loamy soils.

Magnesium (Mg)

Magnesium is important for seed building and the formation of chlorophyll which gives the plants their green colour.

With good magnesium availability, plants can easily absorb phosphorous. Potassium surplus can cause a magnesium deficiency and vice versa. Both nutrients compete with each other.

Magnesium deficiency shows in blotchy leaves with yellow patches between the veins. Leaves like that fall off too early.

Loamy soils are usually rich in magnesium while sandy and mull-rich soils have mostly lower amounts it.

Calcium (Ca)

Calcium influences the soil’s pH value. This is essential as the soil’s acidity regulates how nutrients are released and made available for the plants.

Calcium is important for the plant’s growth and immune system, its nutrient absorption and ripening.

If there is too much calcium in the soil, important trace elements like iron, manganese and boron are bound and unavailable for the plants.

Too little calcium – as is often seen in acid soils – is also harmful. In that case, it can be beneficial to add lime to raise the pH value and add calcium.

But even soils with a normal pH can have calcium deficiency. You can see that when the leaves roll their edges and the shoot tips, buds and young leaves dry out. Calcium deficiency also causes blossom end rot in tomatoes.

Sulphur (S)

Not long ago, soils near towns didn’t show sulphur deficiency due to the emissions of large industrial plants. With receding emissions, the need for sulphur has risen.

Like nitrogen deficiency, sulphur deficiency also results in reduced growth and bleaching of plants. While nitrogen deficiency can first be witnessed in older leaves, sulphur deficiency is first visible in the new, young leaves.

Carefully observe the ratio of nitrogen and sulphur. If you fertilise with nitrogen, you must also increase sulphur.

Plant nutrients: The Micros

Manganese, iron, copper, boron, chlorine, molybdenum and zinc

Often, there are enough trace elements in the soil. If there is a deficiency, however, a high pH value is often the cause.

A deficiency of one or more of those plant nutrients can result in reduced growth and bad harvest yields.

One symptom of iron, manganese and zinc deficiency is that the leaves turn yellowish between the veins. Manganese surplus results in brown stains on the leaves.

Boron deficiency shows by reduced growth of the shoot tips and puny growth of root vegetables Cauliflower may rot from the inside.

Essential substances for plants are macro-nutrients (nitrogen, phosphor, potassium sulpnur, calcium and magnesium) and some trace elements (boron, chlorine, molybdenum, copper, iron, manganese and zinc). The other micro nutrients are not crucial for plants but stimulate their growth.

Balanced nutrients

Learning about plant nutrients can be quite overwhelming at first. The easy method to obtain all the macros, therefore, is to buy some ready-made fertiliser that has a preset ratio of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P) and potassium (K).

What does NPK mean?

On the packaging of an all-round fertiliser, you can find a so-called “NPK number”. One fertiliser, for example, may have an NPK of 12-8-16, indicating that this fertiliser consists of 12 % nitrogen, 8 % phosphorus and 16 % potassium. A more phosphorus-dominant fertiliser could have a ratio of 11-14-17. It’s suitable for flowers and vegetables producing fruit like tomatoes and beans.

Organic versus mineral fertiliser

However, the easy method is not always the best. NPK fertilisers do have their advantages, of course. They are quickly available – both for the gardener and the plant – and you needn’t think much about what to feed your plants. Just throw some fertiliser onto the soil and be done with it.

But, living in a world of duality, some disadvantages cannot be overlooked.

Mineral fertilisers

First, there are two types of NPK fertilisers, mineral and organic. Mineral fertilisers mainly consist of inorganic material in the form of water-soluble salts of chemical origin. In short, they are artificial fertilisers.

They usually work fast but not very long and thus are suitable for first aid in case of nutrient deficiency. Some artificial fertilisers are prepared as long-term fertilisers that release their nutrients slowly and over a prolonged time. If they are overdosed, however, they can have a negative effect not only on the plants but also on the soil, the environment and thus on us.

Although tempting, I don’t recommend using mineral fertiliser in your vegetable garden. The long-term disadvantages for your garden and the environment outweigh the advantages.

Organic fertilisers

Organic fertilisers, on the other hand, mainly consist of substances in organically bound form. The raw materials they are made of either originate from plant or animals. Unlike mineral fertilisers, the plant nutrients in organic fertilisers are not salts that dissolve quickly in water but are “packaged” into organically grown structure. The nutrients are less concentrated but improve the soil and keep the soil organisms happy. Organic fertilisers need some time to work but then they are continuous. Yet, there is also the possibility of overdosing them, leading to the same impacts like with mineral fertilisers. And let’s not put a blind eye to the fact that even organic fertilisers are processed.

In the (yet-to-come) series about natural fertilisers, I’ll show you how you can feed your plants, the soil and all the organisms with purely natural ingredients. Stay tuned.

Health check: Signs of imbalanced plant nutrients

Imbalanced nitrogen

Symptoms: reduced growth, pale or yellow leaves. Older leaves turn yellow fast. The lower leaves turn yellow from the tip, turn brown and dry out. Side roots are badly developed.

Possible cause: nitrogen deficiency

Symptoms: excessive growth, thin stems and shoots. Dark green and excessively large leaves, sometimes with yellow edges. No bloom.

Possible cause: nitrogen surplus

Imbalanced phosphorus

Symptoms: reduced growth, reduced fruit formation. Dark green, sometimes blue-green leaves. Lower leaves have a different colour (yellow, brown or red). The leaves’ underside is brownish/purplish. Leave veins are also brown-purple. Long roots but weak side roots.

Possible cause: Phosphorus deficiency

Imbalanced potassium

Symptoms: reduced growth. Older leaves are yellow-green and striped. Burns and too early transition into hibernation.

Possible cause: Potassium surplus

Symptoms: dry leave edges, sometimes yellow leaves. Older leaves die. Leaves curl and turn yellow-brown. Few and misshapen buds. Long main root but puny side roots. Fruit and vegetables taste bland

Possible cause: potassium deficiency

Imbalanced calcium

Symptoms: reduced growth, pale green leaves

Possible cause: calcium surplus

Attention: calcium surplus may cause magnesium and potassium deficiency!

Symptoms: curled leaves with brown edges. Weakly developed root system. Brown patches on fruit. Blossom end rot at cucumbers and tomatoes. Brown leave edges at lettuce.

Possible cause: Calcium deficiency

Symptoms: the areas between the leave veins turn almost white while the veins stay green. Molybdenum deficiency shows the same symptoms.

Possible cause: Calcium deficiency

When to provide plant nutrients

When you watch any symptomes as described above, you must act and provide your plants with the according nutrient(s).

Apart from that there are plant stages that need special care:

Young growth

If you start your plants from seeds you sow them in a relatively nutrient-poor soil. When they start to grow however and form their first pair of real leaves they become hungry. Now is the time to give them some nitrogen

Newly planted

When it’s time to plant your vegetables out, they benefit a lot from phosphorus and potassium addition.

Blossoming

As soon as the plants develop their first blossoms, they want potassium, phosphorus and calcium to support the formation of blossoms.

Fruiting

All fruit vegetables like tomatoes, cucumbers, zucchini and pumpkins need a sufficient amount of potassium and phosphorus. These nutrients support the formation and healthy ripening of the fruits. Nitrogen is also important but only in small amounts.

Plant nutrients – A necessity

Gardening without nutrients is not possible for long. If you have a good enough soil your plants may grow well for the first one or two years but then they’ll become ill and stagnate or die and you’ll need a magnifying glass to see your harvest. To prevent that scenario you have the responsibility for your plants and soil to feed them according to their needs.

0 Comments